Combustible Dust Bill Introduced

![]() Worker Protection Against Combustible Dust Explosions and Fires Act of 2009 – Requires the Secretary of Labor to promulgate an interim final standard regulating combustible dusts, which shall apply to manufacturing, processing, blending, conveying, repackaging, and handling of combustible particulate solids and their dusts (including organic dusts, plastics, sulfur, wood, rubber, furniture, textiles, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, fibers, dyes, coal, metals, and fossil fuels), but shall not apply to processes already covered by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) standard on grain facilities.

Worker Protection Against Combustible Dust Explosions and Fires Act of 2009 – Requires the Secretary of Labor to promulgate an interim final standard regulating combustible dusts, which shall apply to manufacturing, processing, blending, conveying, repackaging, and handling of combustible particulate solids and their dusts (including organic dusts, plastics, sulfur, wood, rubber, furniture, textiles, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, fibers, dyes, coal, metals, and fossil fuels), but shall not apply to processes already covered by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) standard on grain facilities.

Requires such standard to provide requirements for:

(1) a hazard assessment to identify, evaluate, and control combustible dust hazards;

(2) a written program that includes provisions for hazardous dust inspection, testing, hot work, ignition control, and housekeeping;

(3) engineering controls, administrative controls, and operating procedures;

(4) housekeeping to prevent accumulation of combustible dust in places of employment in depths that can present explosion, deflagration, or other fire hazards, including safe methods of dust removal;

(5) employee participation in hazard assessment, development of and compliance with the written program, and other elements of hazard management; and

(6) providing safety and health information and annual training to employees.

Provides an exemption from otherwise applicable rulemaking requirements for the interim standard but not for the final standard.

Provides that such interim standard shall have the legal effect of an occupational safety and health standard and shall apply until a final standard becomes effective.

Requires the Secretary of Labor to promulgate a final occupational safety and health standard regulating combustible dust explosions that has the same scope and worker protection provisions as the interim rule and provides requirements for:

(1) managing change of dust producing materials, technology, equipment, staffing, and procedures;

(2) building design, such as explosion venting, ducting, and sprinklers; and

(3) explosion protection, including separation and segregation of the hazard.

Requires the final rule to include relevant and appropriate provisions of the National Fire Protection Association combustible dust standards.

Requires the Secretary to revise the hazard communications standard to amend the definition of “physical hazard” to include “a combustible dust” as an additional example of such a hazard.

AIHA offered the following recommendations: 1) “for the periodic inspection and maintenance of engineering controls and equipment, recordkeeping of the results of the inspections, and correction of any problems found during the inspections within a reasonable time.” 2) “determine whether or not it is possible for OSHA to promulgate a final standard within 18 months of enactment of the legislation.”

AIHA offered the following recommendations: 1) “for the periodic inspection and maintenance of engineering controls and equipment, recordkeeping of the results of the inspections, and correction of any problems found during the inspections within a reasonable time.” 2) “determine whether or not it is possible for OSHA to promulgate a final standard within 18 months of enactment of the legislation.”

The letter stressed that while AIHA does not wish to delay a final standard, the association recognizes it could be difficult for OSHA to promulgate a final standard within the 18-month time frame.

Here are some of the information that has been put together based upon the claims of off-gasing from chinese made drywall.

Here are some of the information that has been put together based upon the claims of off-gasing from chinese made drywall. “This document reviews what is currently known about nanoparticle toxicity, process emissions and exposure assessment, engineering controls, and personal protective equipment. This updated version of the document incorporates some of the latest results of NIOSH research, but it is only a starting point. The document serves a dual purpose: it is a summary of NIOSH’s current thinking and interim recommendations; and it is a request from NIOSH to occupational safety and health practitioners, researchers, product innovators and manufacturers, employers, workers, interest group members, and the general public to exchange information that will ensure that no worker suffers material impairment of safety or health as nanotechnology develops.”

“This document reviews what is currently known about nanoparticle toxicity, process emissions and exposure assessment, engineering controls, and personal protective equipment. This updated version of the document incorporates some of the latest results of NIOSH research, but it is only a starting point. The document serves a dual purpose: it is a summary of NIOSH’s current thinking and interim recommendations; and it is a request from NIOSH to occupational safety and health practitioners, researchers, product innovators and manufacturers, employers, workers, interest group members, and the general public to exchange information that will ensure that no worker suffers material impairment of safety or health as nanotechnology develops.” “Research indicates that an appropriately designed and maintained upper-room UVGI system may kill or inactivate airborne TB bacteria and increase the protection afforded to healthcare workers while maintaining a safe level of UVGI in the occupied lower portion of the room. The purpose of this document is to examine the different parameters necessary for an effective upper-room UVGI system and to provide guidelines to healthcare managers, facility designers, engineers, and industrial hygienists on the parameters necessary to install and maintain an effective upper-room UVGI system. These guidelines are consistent with previous CDC healthcare guidelines and expand upon them. This document provides an overview of the current knowledge concerning upper-room UVGI systems and research needs. Information from CDC/NIOSH-funded laboratory studies and other relevant studies is combined in this report to provide guidelines for the installation and use of upper-room UVGI systems. Although other pathogenic microorganisms may be killed or inactivated by upper-room UVGI systems, the guidelines were developed for the installation and use of upper-room UVGI systems capable of killing or inactivating surrogates of mycobacteria.”

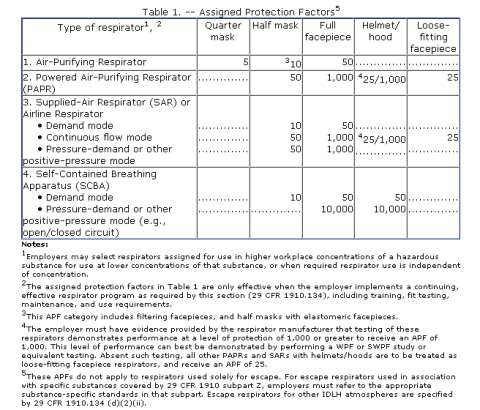

“Research indicates that an appropriately designed and maintained upper-room UVGI system may kill or inactivate airborne TB bacteria and increase the protection afforded to healthcare workers while maintaining a safe level of UVGI in the occupied lower portion of the room. The purpose of this document is to examine the different parameters necessary for an effective upper-room UVGI system and to provide guidelines to healthcare managers, facility designers, engineers, and industrial hygienists on the parameters necessary to install and maintain an effective upper-room UVGI system. These guidelines are consistent with previous CDC healthcare guidelines and expand upon them. This document provides an overview of the current knowledge concerning upper-room UVGI systems and research needs. Information from CDC/NIOSH-funded laboratory studies and other relevant studies is combined in this report to provide guidelines for the installation and use of upper-room UVGI systems. Although other pathogenic microorganisms may be killed or inactivated by upper-room UVGI systems, the guidelines were developed for the installation and use of upper-room UVGI systems capable of killing or inactivating surrogates of mycobacteria.” OSHA has issued a new guidance document for employers who may need to establish and implement a respiratory protection program due to potential exposures to contaminants in workplace air. The document focusues on the mandatory selection provisions of the assigned protection factors (APFs), maximum use concentrations (MUCs) and the use of the APF Table 1 of

OSHA has issued a new guidance document for employers who may need to establish and implement a respiratory protection program due to potential exposures to contaminants in workplace air. The document focusues on the mandatory selection provisions of the assigned protection factors (APFs), maximum use concentrations (MUCs) and the use of the APF Table 1 of