If you work in an facility that creates dust, there are several questions you may be asking yourself regarding combustible dust, including:

- How much dust am I allowed to have on surfaces? Is it 1/4 of an inch, 1/8 of an inch, 1/32 of an inch?

- Am I at risk for a combustible dust explosion?

- How do I test to see if my dust is classified as combustible dust?

- How large of an area can have dust accumulations?

- How do I determine if I can be cited by OSHA under the walking working surfaces standard (1910.22) or the material handling standard (1910.176).

Combustible Dust, Defined

First off, what is a combustible dust? CCOHS provides the following:

Essentially, a combustible dust is any fine material that has the ability to catch fire and explode when mixed with air. Combustible dusts can be from: most solid organic materials (such as sugar, flour, grain, wood, etc.) many metals, and some nonmetallic inorganic materials.

Some of these materials are not “normally” combustible, but they can burn or explode if the particles are the right size and in the right concentration.

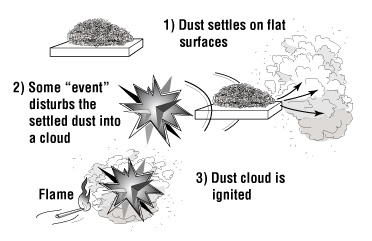

Therefore any activity that creates dust should be investigated to see if there is a risk of that dust being combustible. Dust can collect on surfaces such as rafters, roofs, suspended ceilings, ducts, crevices, dust collectors, and other equipment. When the dust is disturbed and under certain circumstances, there is the potential for a serious explosion to occur. The build-up of even a very small amount of dust can cause serious damage.

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety

Acceptable Accumulation Levels for Combustible Dust

The Combustible Dust National Emphasis Program references 1/32 inch dust accumulation levels, however this is based on some assumptions, including: uniform distribution of the dust and a bulk density of 75 lb/ft3. However, not all dust meets this density (some are lighter, some are heavier). NFPA 654 allows the dust accumulations to exceed the layer depth criteria of 1/32 inch according to the following equation for materials with bulk densities less than 75 lb/ft3.

Additionally, NFPA 654 states that a dust explosion hazard and dust flash fire hazard are deemed to exist in any building or room where any of the following conditions exists:

- The total area of nonseparated dust accumulations exceeding the layer depth (LD) criterion is greater than five percent of the footprint area.

- The area of any single nonseparated dust accumulation exceeding the layer depth (LD) criterion is greater than 1000 ft2.

- The total volume of nonseparated dust accumulations is greater than the layer depth (LD) criterion multiplied by five percent of the footprint area.

- The total volume of any single nonseparated dust accumulation is greater than the layer depth (LD) criterion multiplied by 1000 ft2.

Calculate Allowable Combustible Dust Levels

In order to calculate the level of dust accumulations that may be allowed at workplaces for combustible dust you must know the bulk density. Bulk densities depend on may factors, including the type of material (e.g. wood, paper, plastic, other organics, metal, etc.), the dust particle size, and the dust particle shape. However, OSHA compliance officers must take into consideration the bulk density of the dust prior to determining if there is a violation and subsequent citation.

Very low bulk density materials (e.g. paper dust and corn dust – 25 lb/ft3 and 16 lb/ft3, respectively), may not create a deflagration (heating until it burns away rapidly) hazard even at an accumulation level of 1/4 inch, covering over five percent of the floor area or 1000 ft2, whichever is less. Therefore, facilities should determine their dust bulk densities in order to determine the level of accumulation that does not present a combustible dust hazard.

One of the easiest manners to determine bulk densities is to use an online resource, such as:

The referenced bulk densities can then be plugged into the equation below to determine the allowed LD

Example – Allowed Dust Accumulation

For example, for paper dust with a bulk density of 25 lb/ft3, the layer depth criterion is approximately 1/10th of an inch.

Therefore, in this example, a dust explosion hazard and dust flash fire hazard are deemed to exist if:

- The total area of non separated dust accumulation exceeding 1/10th of an inch over greater than 5 percent of the footprint area, or

- The area of any single nonseparated dust accumulation exceeding 1/10th of an inch is greater than 1000 ft2, or

- The total volume of non separated dust accumulations is greater than 1/10th of in inch multiplied by five percent of the footprint area, or

- The total volume of any single nonseparated dust accumulation is greater than 1/10th of an inch multiplied by 1000 ft2.

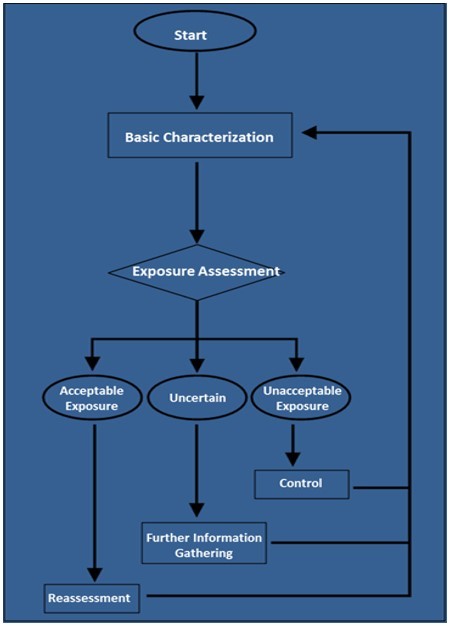

How Does OSHA Evaluate Dust Accumulations?

It should be noted that OSHA compliance officers will only likely send samples out for bulk density determination if the material is light (e.g. paper dust, fabric fibers) and the levels of accumulation exceed 1/4 of an inch over 5% of the floor area of a room or building, of 1000 ft2, whichever is less.

However, if dust accumulations are documented to exceed one inch in depth (extending over 5 percent of the floor area or a room or building, or 1000 ft, whichever is less), samples of dust don’t need to be submitted for bulk density determination. The OSHA compliance officer can use the referenced sources as guidance to determine the approximate values for LD and can issue citations without the bulk density determination.

Source: OSHA – Evaluating Hazardous Levels of Accumulation Depth for Combustible Dusts